Can TMS Be Used to Treat Alzheimer's Disease?

Alzheimer’s disease is a complex brain disease that results in the progressive deterioration of one’s cognitive, emotional, and behavioral capacities. The condition affects nearly six million people in the United States age 65 and older.

Alzheimer’s disease is a complex brain disease that results in the progressive deterioration of one’s cognitive, emotional, and behavioral capacities. The condition affects nearly six million people in the United States age 65 and older.

Though there is no cure for AD, many treatments offer some amount of symptom reduction. While they are effective to some degree, there is much room for improvement.

In recent years, researchers have been exploring alternative ways of addressing the range of impairments caused by AD. In particular, they have explored whether transcranial-magnetic stimulation (TMS), a non-invasive, nonpharmacological procedure often used for psychiatric conditions such as treatment-resistant depression, may prove useful against the cognitive and emotion impairments experienced by individuals with AD.

If effective, this novel application of TMS could help AD patients maintain their capacities and improve their quality of life. Does the evidence support its use?

What is TMS?

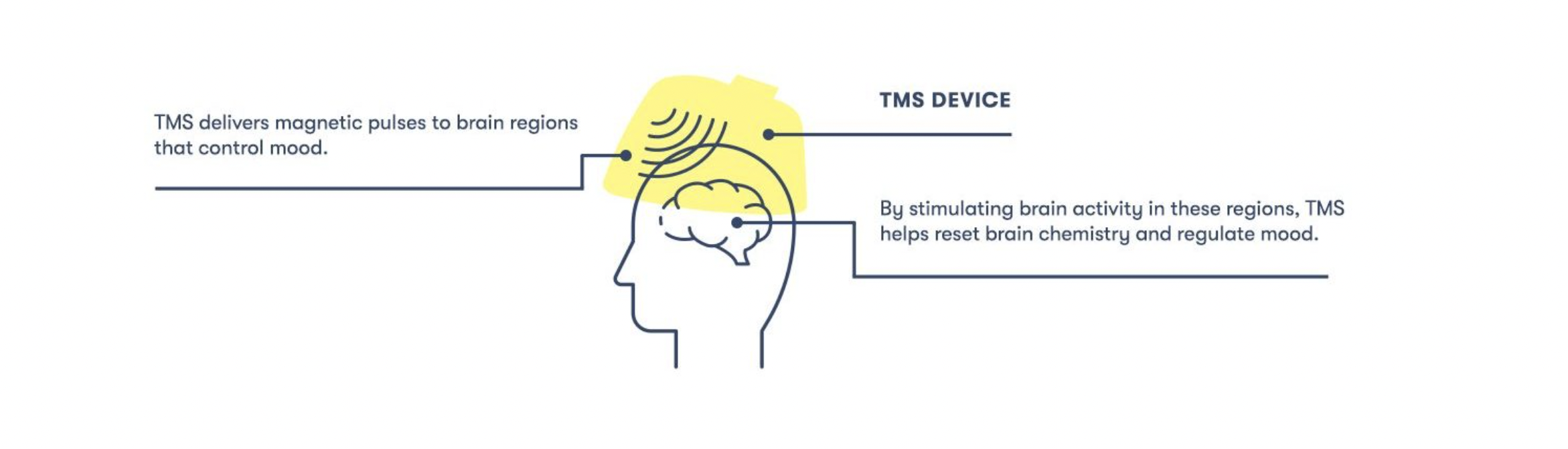

Transcranial magnetic stimulation is a drug-free and noninvasive procedure used to treat various brain disorders, including several mental health conditions. It uses magnetic coils placed just above the scalp to send magnetic pulses into specific regions of the brain associated with symptoms of the condition it is being used to treat. For example, in the case of treatment-resistant depression, the pulses are sent toward regions of the brain associated with mood regulation.

By sending repeated pulses to these specific areas of the brain, TMS “trains” neurons in those locations to fire differently and create new, healthier connections.

Assessing the Efficacy of TMS for the Treatment of AD

TMS has been used to treat a wide range of issues associated with AD with varying degrees of efficacy and evidence backing its use.

TMS for Mood-Related Symptoms of AD

Though Alzheimer’s disease is mainly known for its effects on memory and cognition, it can also cause disruptions in mood and emotional regulation. For example, up to fifty percent of individuals with AD suffer from depression.

Though the high prevalence of depression in AD patients is partially attributable to the stress of having the disease, it is likely also to be the direct result of the disease’s biological effects. For example, post-mortem studies have found that AD patients with depression were more likely to have lost neurons that respond to chemical messengers commonly targeted by anti-depressants, such as serotonin and norepinephrine.

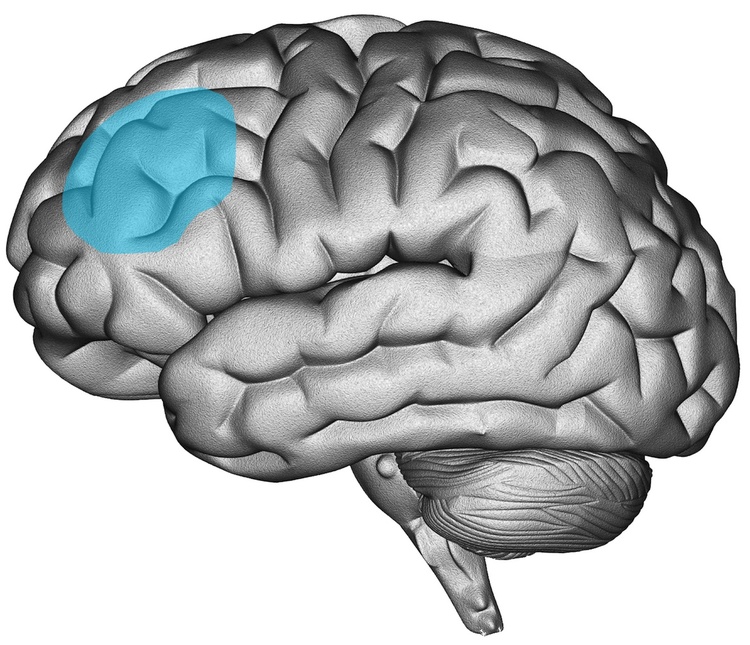

Several studies have found that AD patients treated with TMS experience improvements in their mood. For example, TMS has been associated with lower scores of depression and apathy among individuals with AD. This finding is supported by the fact that the treatment protocol for AD often targets the same brain area as the protocol for treatment-resistant depression, namely the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (L-DLPFC).

TMS for the Cognitive Symptoms of AD

Regarding cognitive symptoms, researchers are actively investigating whether and how much TMS helps. In particular, they have examined the effects of TMS on the following:

- Memory (facial recognition, word recall, etc.)

- Language function (e.g., sentence comprehension)

- Executive function (e.g., verbal reasoning, problem-solving, planning, etc.)

- Visuospatial skills (e.g., the ability to draw a clock)

While several studies have found positive results, others have failed to find a significant effect. Explaining this is difficult mainly because different researchers have utilized different protocols on different parts of the brain in patients at different disease stages. As a result, it is hard to determine whether the results are inconsistent because the treatment does not work or because some researchers are targeting the right areas in the right ways in the right patients while others are not.

Researchers have attempted to comb through the data to find patterns in when the treatment does and does not work. One finding that emerged most clearly is that TMS does not work in patients with more advanced AD, suggesting that if the treatment works at all, its efficacy depends on the individual’s disease stage.

Even among the studies that have found positive results, patients may have improved for reasons that had nothing to do with the direct effect of TMS on AD. For example, improvements in depression are associated with gains in cognitive performance. Since TMS tends to alleviate depression in AD patients, this could explain why their cognitive symptoms improved and not that TMS treated the part of their cognitive dysfunction caused by their AD.

Another issue stems from how the studies measure the subjects’ cognitive abilities. To determine whether symptoms improved over time, researchers had AD patients repeatedly take tests and perform tasks that allowed them to track how their performance changed as they continued to receive TMS. The problem with this method is that patients may get better with practice alone. This means we can’t be sure how much the positive effects are attributable to practice or to the impact of TMS on AD itself. While some studies included a control group that took the cognitive assessments while being given “sham” TMS, which does not stimulate the brain, the results were unclear.

Conclusion

So, does TMS work for Alzheimer’s disease? That depends in part on what symptoms we are concerned with. As far as depression goes, TMS appears to work just as well in AD patients. However, the results are less clear when it comes to cognitive impairments. Confounding variables and a lack of consistency in treatment protocols mean it’s too early to draw any confident conclusions.

If you feel you need to see a mental health professional or could use help deciding which service is right for you, please give us a call at 805-204-2502 or fill out an appointment request here. We have a wide variety of providers, including therapists, psychiatrists, nurse practitioners, and nutritional therapists, who can see you in as little as one day via teletherapy.

Want to find out if Heading is right for you?

Complete our consultation form and an intake specialist will get in touch.

I’ve always struggled to get myself to try new things. I like consistency and predictability, and new experiences get in the way of maintaining my desired level of stability.

I’ve always struggled to get myself to try new things. I like consistency and predictability, and new experiences get in the way of maintaining my desired level of stability.

When people experience grief, they may not outwardly make their feelings known. It can be difficult to know exactly what to say and easy to interpret someone’s silence as “ok-ness.”

When people experience grief, they may not outwardly make their feelings known. It can be difficult to know exactly what to say and easy to interpret someone’s silence as “ok-ness.”

Veteran’s Day allows us to explore and assess how we can better support our veterans, especially when navigating their mental health. Recent research suggests 11 to 20 percent of veterans experience post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in a given year. Suicide rates of military service members and veterans are also at an

Veteran’s Day allows us to explore and assess how we can better support our veterans, especially when navigating their mental health. Recent research suggests 11 to 20 percent of veterans experience post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in a given year. Suicide rates of military service members and veterans are also at an

Though often used interchangeably, grief and mourning are notably different, and each plays a critical role in how we react to death and loss. Psychology Today distinguishes mourning as

Though often used interchangeably, grief and mourning are notably different, and each plays a critical role in how we react to death and loss. Psychology Today distinguishes mourning as  Cultural rituals related to the grief and mourning process can help create predictability in a time of uncertainty. For many, these cultural norms are a sense of support, whereas for others, it may be a source of conflict if their current beliefs, or the beliefs of the deceased, are misaligned with the cultural norms. So the question is, what is normal when it comes to grief and mourning?

Cultural rituals related to the grief and mourning process can help create predictability in a time of uncertainty. For many, these cultural norms are a sense of support, whereas for others, it may be a source of conflict if their current beliefs, or the beliefs of the deceased, are misaligned with the cultural norms. So the question is, what is normal when it comes to grief and mourning?  For as much togetherness as many cultural norms bring to the grieving process, grief is also individualized and sometimes isolating. But there are means to seek support to help ease the feelings of loneliness, confusion, and isolation that can accompany grief. Seeking support and comfort in the predictability and structure of cultural norms can help ease the process of grief and the tasks of mourning. Seeking therapy can also help normalize and validate the thoughts, emotions, behaviors, and timelines associated with grief and mourning in both a cultural and individual context.

For as much togetherness as many cultural norms bring to the grieving process, grief is also individualized and sometimes isolating. But there are means to seek support to help ease the feelings of loneliness, confusion, and isolation that can accompany grief. Seeking support and comfort in the predictability and structure of cultural norms can help ease the process of grief and the tasks of mourning. Seeking therapy can also help normalize and validate the thoughts, emotions, behaviors, and timelines associated with grief and mourning in both a cultural and individual context.

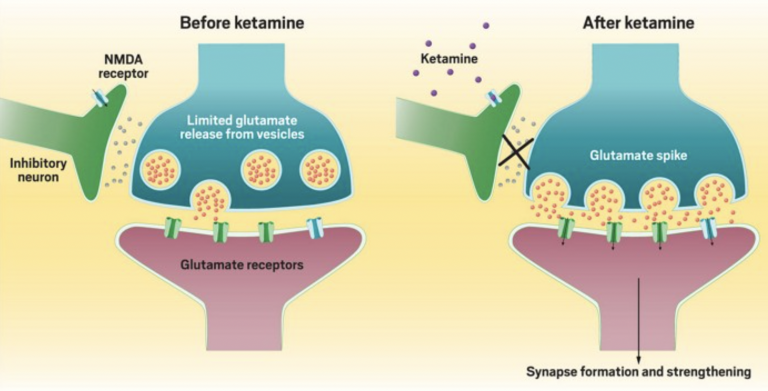

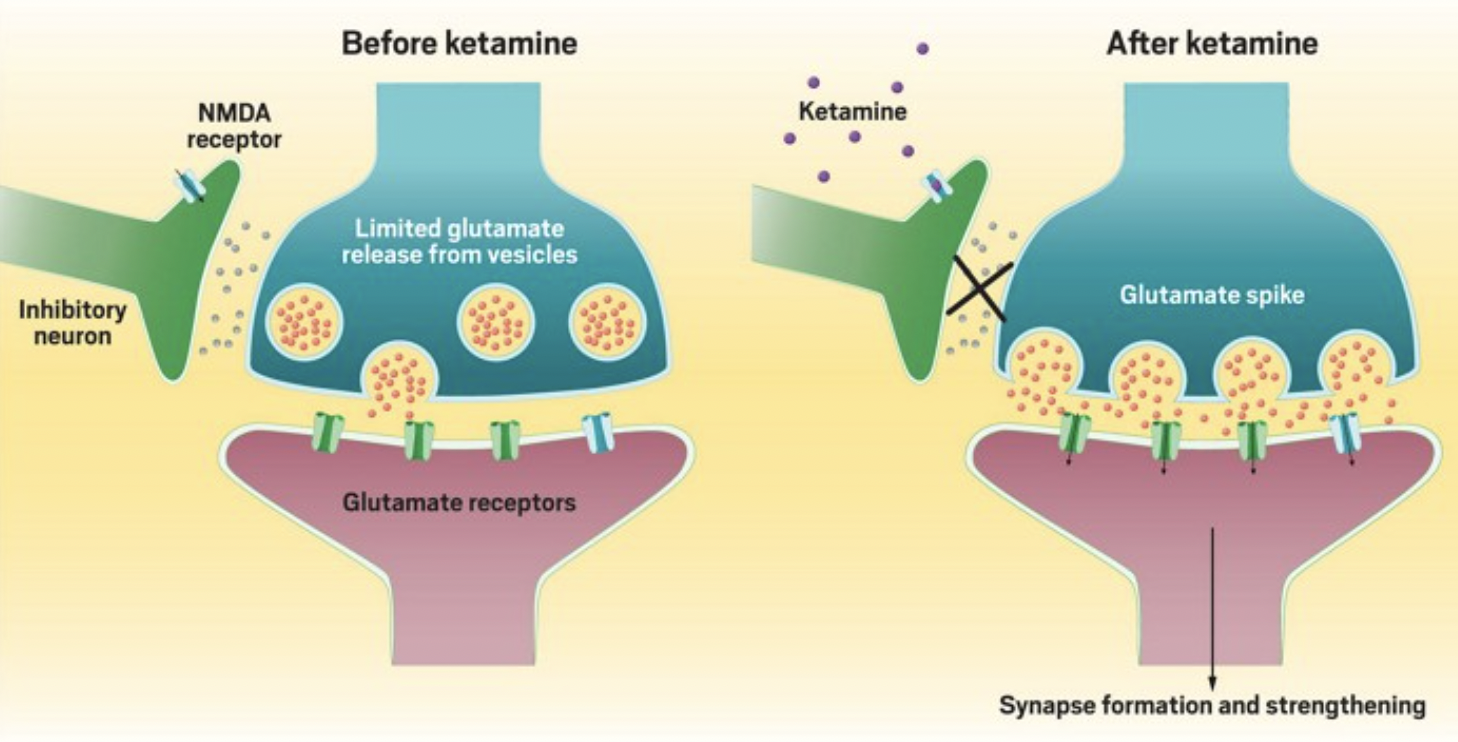

Over the past few years, psychedelics such as LSD and psilocybin mushrooms have garnered much attention as researchers explore their potential use in treating mental health conditions.

Over the past few years, psychedelics such as LSD and psilocybin mushrooms have garnered much attention as researchers explore their potential use in treating mental health conditions.  Though there is much disagreement about what counts as a psychedelic, it’s generally accepted that they must induce specific mind-altering effects. Some argue this is all that is required. In other words, they claim that as long as the substance causes a “psychedelic experience,” then it’s a psychedelic.

Though there is much disagreement about what counts as a psychedelic, it’s generally accepted that they must induce specific mind-altering effects. Some argue this is all that is required. In other words, they claim that as long as the substance causes a “psychedelic experience,” then it’s a psychedelic.